Next: Particle in a box Up: Quantum Mechanics Previous: Electron diffraction experiment Contents

From the de Broglie hypothesis, we can quickly predict the outcome of many experiments with elementary particles. The first experiment we shall consider demonstrates something very unusual about elementary particles known as the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle. This principle what we mean by ``small'' in the idea of the classical limit and is useful in giving quick estimates of quantum mechanical effects.

The basic idea comes from what we already know about the intensity of waves after passing through any opening. The notes on interference show that the intensity of waves passing through a finite slit exhibit the phenomenon of diffraction: no matter how straight the waves approach the opening, on the other side the intensity spreads out over a range of angles. From the de Broglie hypothesis, we expect the same behavior for the probability of finding particles. This has some unusual implications.

Figure 5 shows an experiment where particles of

momentum ![]() are sent directly toward a slit of width

are sent directly toward a slit of width ![]() and

then collected on a observation screen at a large distance

and

then collected on a observation screen at a large distance ![]() from the slit. From the de Broglie hypothesis we have the immediate

result that particles arrive at the screen with all possible random

angles

from the slit. From the de Broglie hypothesis we have the immediate

result that particles arrive at the screen with all possible random

angles ![]() with the same pattern we found for the interference

pattern from a single slit (from LN ``Wave Phenomena II:

Interference'')

with the same pattern we found for the interference

pattern from a single slit (from LN ``Wave Phenomena II:

Interference'')

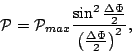

|

(8) |

For this type of experiment, the classical physics prediction is that all

particles should arrive on the screen at the angle ![]() . Consistent

with the concept of the classical limit, this is the most

probable outcome. However, some particles will hit the screen

at almost all angles, with the exception of just a few special points where

the probability just happens to be zero. This means that every time a

baseball is thrown through a door, even in vacuum so that there is nothing

to disturb the path of the ball, there is some chance that it will take a

sharp turn on the other side.

. Consistent

with the concept of the classical limit, this is the most

probable outcome. However, some particles will hit the screen

at almost all angles, with the exception of just a few special points where

the probability just happens to be zero. This means that every time a

baseball is thrown through a door, even in vacuum so that there is nothing

to disturb the path of the ball, there is some chance that it will take a

sharp turn on the other side.

To see how this is not inconsistent with the observations of our daily

lives, it helps to figure out what range of angles are most likely.

The probabilities in Figure 5 tend to be rather

small after the first minima bounding the central maximum. In fact,

over 90% of the area under the curve is contained in the main peak

between these first minima. Thus, with better than 90% certainty, we

can say that the particle will arrive at angles in the range

![]() , so that

, so that

![]() . Using the definitions of

. Using the definitions of ![]() and

and ![]() above, this

gives

above, this

gives

![]() . Thus, the reasonably expected range of

angles is

. Thus, the reasonably expected range of

angles is

Heisenberg realized that this phenomenon of spreading out after being

restricted through an aperture is very general and found a very useful

way of expressing the result in terms of classical concepts about

particles. The slit in Figure 5 restricts the

particles to a range of values ![]() in the

in the ![]() -direction.

The fact that the particles can then be found on the screen at angles

-direction.

The fact that the particles can then be found on the screen at angles

![]() means that after being restricted by the slit in the

means that after being restricted by the slit in the

![]() -direction, the particles now pick up random (!) momenta

-direction, the particles now pick up random (!) momenta ![]() in

the

in

the ![]() -direction of value which the geometry of

Figure 5 determines to be

-direction of value which the geometry of

Figure 5 determines to be

![]() .4 The likely range in these random momenta

is thus

.4 The likely range in these random momenta

is thus

![]() ,

where we have used the likely range of angles from Eq. (9).

Note that this range becomes greater and greater in inverse proportion

as

,

where we have used the likely range of angles from Eq. (9).

Note that this range becomes greater and greater in inverse proportion

as ![]() decreases. Heisenberg described this effect by saying that the

act of constraining a particle to a region of size

decreases. Heisenberg described this effect by saying that the

act of constraining a particle to a region of size ![]() along

the

along

the ![]() -direction results in an uncertainty in its momentum

-direction results in an uncertainty in its momentum ![]() so that

so that

![]() is at least as big as some

constant. (He said ``at least'' as big because it is always possible

to introduce additional sources of uncertainty beyond the fundamental

limit.) In this case, multiplying our results, we find the constant

to turn out to be

is at least as big as some

constant. (He said ``at least'' as big because it is always possible

to introduce additional sources of uncertainty beyond the fundamental

limit.) In this case, multiplying our results, we find the constant

to turn out to be ![]() .

.

A few technical notes are in order. In defining the uncertainty

![]() , we used the range of momenta for which we have 90%

confidence. The precise definition used in advanced courses in

quantum mechanics is to use the standard deviation statistic that we

use in the analysis of exam scores, which gives a somewhat narrower

measure for

, we used the range of momenta for which we have 90%

confidence. The precise definition used in advanced courses in

quantum mechanics is to use the standard deviation statistic that we

use in the analysis of exam scores, which gives a somewhat narrower

measure for ![]() . Also, a ``smoother'' slit where the

particle has some chance of making it through the edges can also

lessen the uncertainty in

. Also, a ``smoother'' slit where the

particle has some chance of making it through the edges can also

lessen the uncertainty in ![]() . Finally, we could just as

easily aligned our slit with the

. Finally, we could just as

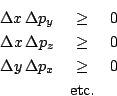

easily aligned our slit with the ![]() -axis. When all of this is taken

into account, the precise mathematical statement has been shown to be

that we have separately for each component

-axis. When all of this is taken

into account, the precise mathematical statement has been shown to be

that we have separately for each component ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() that

that

Tomas Arias 2004-11-30